Vinyl, as a music-storage format: the tangible and the intangible lure of long-playing records

We asked renowned technology journalist Simon Lucas to share his passion for vinyl with us.

If you love music and vinyl as much as we do you will enjoy Behind The Counter, a 12-part video series celebrating the unique culture of independent record stores across the UK and US, shining a light on the instrumental role that they play in bringing music to fans in their communities. Watch the first episode here.

We asked renowned technology journalist Simon Lucas to share his passion for vinyl with us.

75 years, it goes without saying, is an eternity where technology of any kind is concerned. And it’ll soon be three-quarters of a century since Columbia Records first whipped the covers off its thrilling new music storage format: the 12in vinyl record. The world was almost immediately in thrall, both to its modernity and to its possibilities. 20 minutes of music per side! A mere 33.3 revolutions per minute! Discs that don’t smash if you drop them! Compared to the 10in shellac 78rpm disc it supplanted, the long-playing vinyl record was not so much a technology at the cutting edge, more like a time-traveller from the future.

Ever since that Columbia Records press conference at the Waldorf Astoria in New York during June of 1948, there have been numerous and concerted efforts to declare the vinyl format deceased. Storage formats both analogue and digital, both physical and virtual, have tried to nail the lid down on the LP. But this is the format that will not die.

How has the vinyl format managed to dodge the coffin all these years? After all, it’s big and bulky - which means it needs a lot of storage space. It’s almost laughably easy to damage - in fact, you’re damaging it simply by playing it. And regardless of how impressed they were in 1948, having to get out of your seat every 20 minutes (maximum) to turn a record over is hardly conducive to a relaxing time. Is it? So why has the LP hung in there while smaller, more convenient, more robust and - let’s not beat about the bush here - less expensive formats have perished?

I think the reasons fall broadly into three categories: the sonic, the tactile and the emotional. Nothing empirical, you’ll notice - all subjective to a lesser or greater extent. But just because these reasons aren’t rooted in facts and figures, that doesn’t make them any less compelling. In fact, they might even be more compelling because they’re so abstract.

Of course, the whole point of long-playing records is as a music storage device - so if LPs didn’t sound acceptable they’d never have made it to 1950, let alone deep into the 21st century. But vinyl is routinely held up as the pinnacle of audio satisfaction - and while the definition of ‘good sound’ is open to interpretation, for my money (and Lord knows I’ve spent enough of it on LPs) vinyl records bring the listener closer to what an artist, a producer and a recording engineer intended than any alternative format.

No, the sound of vinyl isn’t perfect. It can tend towards the lush and warm-ish, and that’s before the stylus has even collected any fluff. An indifferent music system with a turntable as a source can sound vague and ponderous, just as an ill-sorted system using compact disc as a source can sound edgy and hard. But when it’s properly implemented, the sound of a vinyl-based system has greater weight and momentum, greater unity and integration, greater detail and greater dynamism than any alternative. The sensation of a collection of musicians all responding sympathetically to each other, all behaving with the same commonality of purpose, all bearing down on a piece of music in an effort to give it lift, is more apparent with vinyl than with any other format.

In fact, I think it’s the ability to deliver a recording of numerous disparate elements as a unified whole (what is often, and vexatiously, referred to as ‘timing’) that really sets vinyl apart in terms of sheer musicality. It’s the sonic equivalent of the murmuration of starlings: an understanding of an overall pattern of movement and how each discrete element is incorporated. It’s a kind of audio telepathy.

(I should point out - in case it’s not blindingly obvious - that I am not an engineer, and consequently have no idea why vinyl should lend itself to reproducing music in such a naturalistic and effortlessly affecting way. But then I don’t have any real idea of how it’s possible to translate varying depths and widths of a groove etched into a piece of vinyl into sound, either. I am, however, confident in my abilities to properly assess the results of this ancient process.)

The tactility of long-playing records isn’t quite as crucial as the sound they make, of course, but it nevertheless goes a long way to reinforcing the allure of vinyl as a format - I don’t think the ‘hands-on’ element of a vinyl-based music system can be overstated.

The difference between yelling “hey Google - play Hello Earth by Kate Bush” at a smart speaker and taking your copy of Hounds of Love from the shelf, slipping the record from its inner sleeve, putting it on the turntable and lowering the tonearm onto the correct section of the vinyl is, I reckon, roughly the same as the difference between the taste of a service-station sandwich and the flavour of a meal you cooked yourself. The ritual is important, the literal sensuousness of the process is important, the investment of oneself in the procedure is important. It’s dynamism upon dynamism - the artist and her assistants have engaged in a process, and now you as a listener have a role to play in it too.

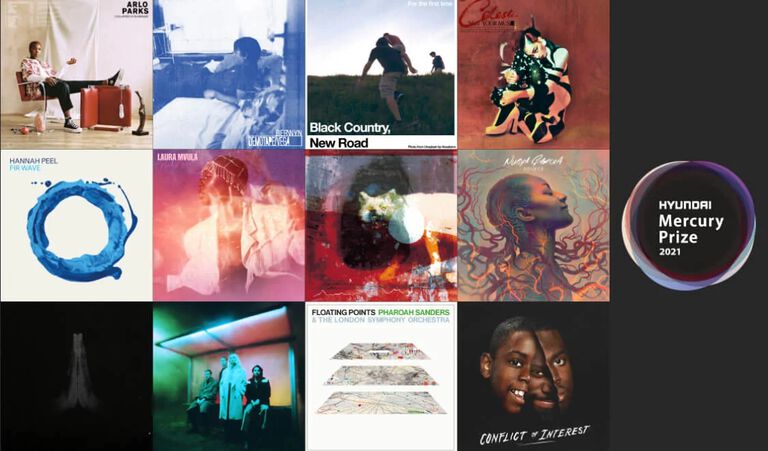

Plus, of course, once the beautifully recorded and beautifully reproduced music is playing, there is the big, square album sleeve to be investigated. There are liner notes to be read, credits to be pored over, lyrics to be digested. Did you ever buy a frame in order to put the covers of your favourite compact discs on the wall? Of course you didn’t. In fact, are you even sure what the artwork that accompanies your favourite recordings looks like if you’ve only experienced it in compact disc form? And don’t get me started on the poverty of the music streaming service experience where this sort of thing is concerned. What does the artwork to the cover of Hounds of Love look like when you’re listening to it on Spotify via your smartphone? That picture is there on that sleeve for a reason, and if you don’t know what it looks like then you’re missing out on part of the experience the artist wants to share with you.

‘Tactility’ has started to blur into the ‘emotional’ now, hasn’t it? But maybe the entire thing is about ‘emotion’ really - after all, what’s music for if not to move you, in some sort of way, on an emotional level? Want to feel euphoric? Melancholic? Transported in one of numerous other directions? Music will do that for you more directly and more viscerally than any other art form, and the more it truly sounds like music the more pronounced the effect will be.

But vinyl loads more emotional baggage onto the listener than simply its ability to mainline the musical experience. There’s the olfactory - who doesn’t enjoy a good sniff of a record collection? Takes you back, doesn’t it? It might be a relative who had a lot of LPs in their house, it might be a cupboard at school where the music teacher kept all the vinyl out of harm’s way, it might be that record shop you used to hang around when trying to decide how to spend your hard-earned. They all smell of records, and it’s an evocative aroma. Ever been to a record fare? The odour of the massed stock is enough to make me giddy.

Buying a record and taking it home can be an emotional experience, too. There’s no doubt the ritualistic element of taking my pre-driving licence self into the city centre, getting amongst ‘my people’ in the record shop, making and paying for my selection and then slipping it into the carrier bag before heading back to the railway station was a pivotal part of my adolescence (and, let’s face it, well beyond). Make sure the cover is facing outwards so any casual observer will understand just what a judicious individual I am - and be sure to have a good stare at other folks’ bagged records too, in order to feel kinship or superiority.

Yes, I’ve damaged records - I’ve scratched them irreparably, usually because I’ve tried playing them while in an advanced state of refreshment. I’ve carelessly left them in sunlight or near heat, and they’ve warped to the point they could be used as flowerpots. Once I sat on one, and that was the end of that. Yes, my record collection takes up way too much space in my home - and among the occupants of my home, opinion as to its decorative credentials is strongly divided.

I find this in no way off-putting, though. I love music, for the same reasons we all love music. But I never love it more than when it’s being gifted to me by a vinyl record.

Browse some of our related articles

Celebrating independent record stores