Bowers & Wilkins: How it began

The early history of the world’s best-known and most acclaimed loudspeaker company is a fascinating tale of obsession for the very best – mixed with the occasional stroke of good fortune.

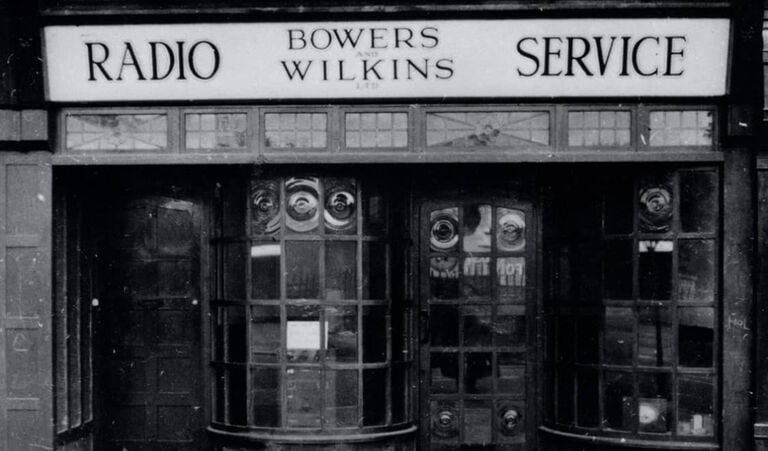

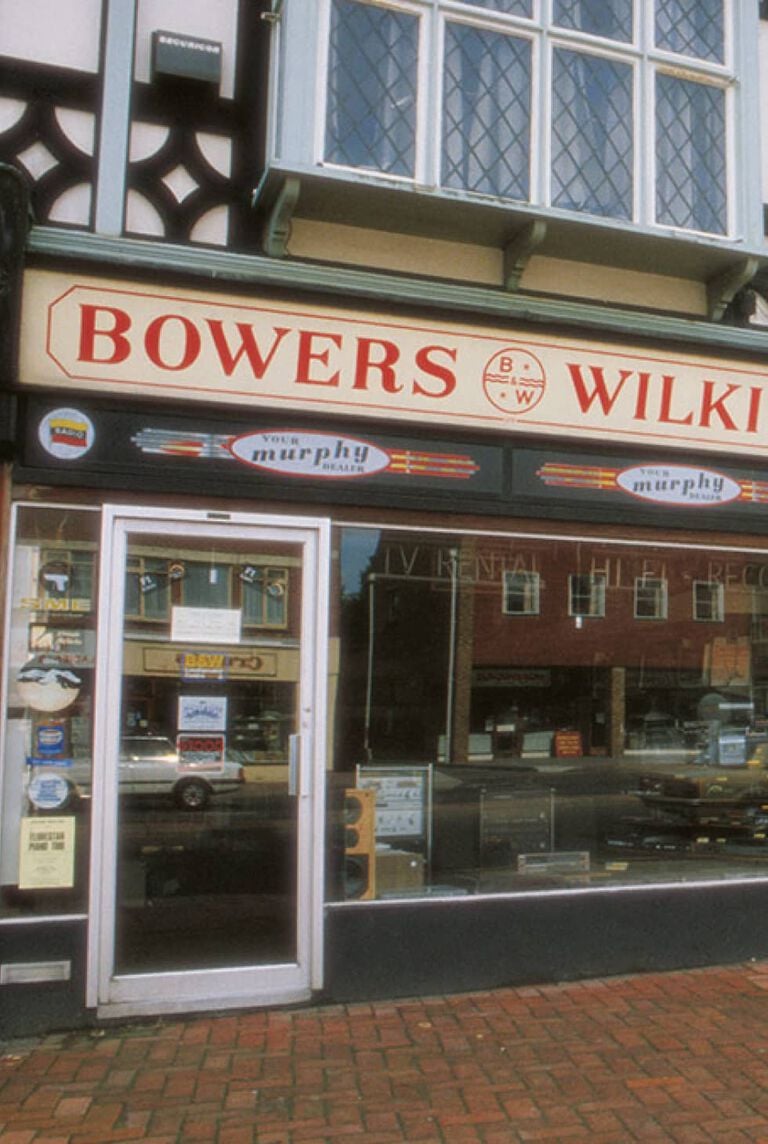

It began with a friendship formed in the armed forces in World War II, blossomed into a small radio and TV shop in the English seaside town of Worthing, named itself to avoid confusion with a cigarette company, and owes its existence to a satisfied customer and her generous bequest. The early history of the world’s best-known and most acclaimed loudspeaker company is a fascinating tale of obsession for the very best – mixed with the occasional stroke of good fortune.

Our story begins in World War II, with Worthing resident John Bowers joining the Royal Corps of Signals at the age of just 17. His expertise and enthusiasm for all things radio quickly attracted attention and soon, he was recruited into the Secret Intelligence Service, also known as MI6. Bowers was stationed at Whaddon Hall, an offshoot of Bletchley Park; along with his colleagues – including Roy Wilkins – he was tasked with maintaining clandestine radio contact with British agents and resistance fighters in occupied Europe.

John Bowers

Bowers & Wilkins, Worthing

The two men became firm friends and quickly concluded that after the war, they would go into business together. After VE day they opened a small shop in Bowers’ home town of Worthing in August 1946, to serve the growing numbers of amateur radio enthusiasts – it was something of a craze at the time, and older readers will remember Tony Hancock’s neighbour crying out ‘Would you stop playing with that radio of yours, I'm trying to get to sleep!’ in the classic comedy The Radio Ham. Over time, the shop went on to offer audio components such as amplifiers and speakers, plus, later on, televisions – not just selling sets but also renting them, in the days when TVs were too expensive to buy. To support the business, the shop also set up a repair workshop, run by Peter Hayward, and it was in this workshop that it also grew its business in public address systems, supplied to the likes of schools and churches across the local area.

As a result of all this expansion, John Bowers’ interests began to come more to the fore: he was dissatisfied with the sound of many commercially available loudspeakers, especially when playing his beloved classical music, and felt no system he had heard could convey the experience of listening to a solo piano, or indeed recreate the live experience. So he started to modify existing designs to bring them closer to what he wanted and selling them, in strictly limited quantities, to his loyal customer base.

This small speaker production line in the back of the shop started to gain a reputation, with Bowers-modified designs finding favour with discerning customers in the Worthing area. As a result, he began spending ever-more of his time analysing and designing speakers, until, in a significant and life-changing moment in 1966, one of his discerning customers finally gave him the impetus to turn his sideline into a full-time business. A Miss Knight, a wealthy Worthing resident and former opera singer, left Bowers £10,000 in her will – the equivalent of almost £200,000 now – to pursue his loudspeaker business. It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and, a result, Bowers relinquished his role at the shop to concentrate on his passion for speaker design, taking with him Peter Hayward, while Roy Wilkins took over sole responsibility for the shop. However, a Wilkins did join the new loudspeaker business – Roy’s son Paul went to work for Bowers, becoming Director of UK Sales.

At first, B&W Loudspeakers Ltd was set up in some garages at the rear of the shop, which were reconfigured into design, production, measurement, and dispatch departments. The final move to new premises wouldn’t happen until 1969. And with Bowers & Hayward at the helm of the new company, why did it retain the ‘B&W Loudspeakers’ name? Well, Bowers & Wilkins had already built itself a decent reputation – albeit a fairly local one. Company lore also suggests Bowers was keen not to fall foul of tobacco company Benson & Hedges, which was already using the B&H title!

The philosophy of the new company’s speaker design was simple – John Bowers said that ‘The best loudspeaker isn’t the one that gives the most, it’s the one that loses the least.’ There are great parallels with the famous mantra of racing car designer Colin Chapman, who said the secret of his work was to ‘Simplify, then add lightness’, but Bowers wanted his speakers to be ‘to the ear what a flawless pane of glass is to the eye, allowing the clear passage of a sensory image, uncorrupted and faithful in every last nuance to the original.’ That belief, distilled down to the simple ‘True Sound’, is what guides the design and engineering of Bowers & Wilkins loudspeakers to this day.

The best loudspeaker isn’t the one that gives the most, it’s the one that loses the least.

–John Bowers

In the search for this ideal, the profits from the company’s first speaker, the floorstanding P1, were invested in a collection of audio test equipment, the better to understand what would make an ideal loudspeaker – and of course this new insight meant that an improved version, the P2, followed very shortly, each pair being delivered with its own calibration certificate. Those ‘second generation’ speakers retained the EMI-made midrange and bass drivers of the original, but Bowers was already innovating: the P2 had an ionophone tweeter, delivering high frequencies – up to 50kHz – by ionising air particles at very high temperatures. However, it wasn’t a complete success: the modulator it required didn’t get on too well with TV pictures, however hard the company tried to screen it!

Even in those early days, Bowers was known as an enthusiastic acquirer of the latest measuring equipment, as he strove to gain even more insight into what speakers did, and how they could be made to do what he wanted. A colleague from those early days recalled that ‘The [measuring equipment company] Brüel & Kjær rep used to pop into us with the latest bit of kit, and John would usually say: “yep, I’ll have that, leave it here”.’

All this measurement and analysis – still a major part of the Bowers & Wilkins philosophy, as the company continues to invest in state-of-the-art measurement and continually expand our understanding via our own research establishment – brought about the first Bowers & Wilkins speakers aimed at people like Bowers: the serious classical music fans. The DM1 – the prefix stood for ‘domestic monitor’ – again used bought-in drivers, but Bowers was already realising that the way forward was to design and build his own drive units. So he did the only logical thing: he hired EMI’s technical manager responsible for the drive units the company had been using, Dennis Ward.

The DM70 was a revolutionary result of all these talents coming together, combining a 30cm bass driver in its own enclosure with an 11-element curved electrostatic panel for the midband and treble: no question here of taking the easy route to a better speaker, and it was all made in-house. And really made-in house: Steve Roe, who joined the company in the early 70s, recalled that ‘We used to all make DM70s by hand, myself along with John Bowers and the draughtsman Ron Greenwood – the three of us used to make the electrostatic units.’

DM70

Kenneth Grange

The speaker became a critical and sales success, living up to the Bowers adage that ‘If you can make a better product, you can sell it,’ and as part of that thinking industrial designer Kenneth Grange was brought on board to improve the way the products looked, this co-operation led to the DM6, known in some quarters as the ‘Pregnant Penguin’ thanks to its ‘stepped’ arrangement of tweeter, midrange and bass unit.

Whatever the nickname, the DM6 proved a hugely popular design, one still sought after by collectors, and also saw the arrival of another element that sets the company’s designs apart to this day – the investigation of innovative materials in the quest for even greater performance. The DM6 was the first model to use the Aramid Fibre woven midrange cone that would become a mainstay of Bowers & Wilkins designs for more than decades, leading to lots of explanations of ‘yes, as used in racing cars and bulletproof vests’.

DM6

Queen’s Award for Industry for export achievement

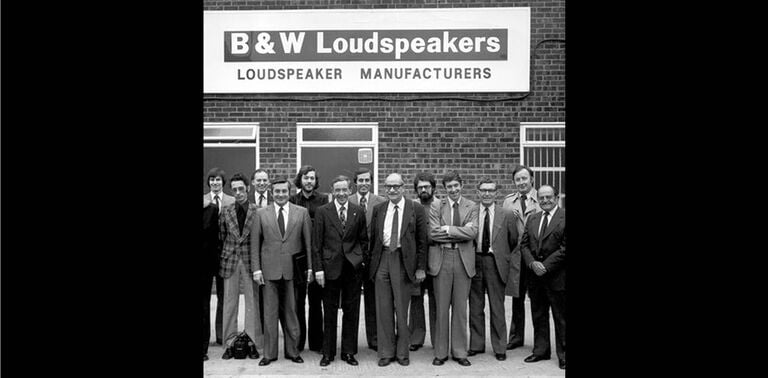

The company continued to grow, and spread its market worldwide – by 1973, when 60% of its production was exported, it collected its first Queen’s Award for Industry for export achievement, with a second in 1978 when that figure had risen to 90%. By then, it had expanded out of the original garages and into purpose-designed premises, with its own anechoic chambers for speaker measurement, and a mass of measuring equipment.

With the growth of their insights into design, acoustics and production, in 1979 came not only the company’s most ambitious product to date, but the one which would go on to define everything Bowers & Wilkins stands for right up to the present day – and beyond: the 801.

Remember by this stage the company was only 13 years on from that generous bequest from Miss Knight – yet the 801 was rapidly adopted as the reference monitor for some of the world’s greatest recording studios, including Abbey Road, Skywalker Sound, Decca and Deutsche Grammophon. From modifying speakers in the back of a radio and TV shop to becoming the sonic reference for much of the recording industry in such a short time was no mean achievement – but John Bowers was only just getting started…